COLIN BRANT | Paintings _ Exhibitions _ Writing _ About _ Contact _ @colinbrant724

Bob Nickas: Colin Brant, Phantom Ship, New York Art Critics Association, June 13, 2025

Most would be surprised to know that this artist doesn’t consider himself a landscape painter, given the many sites, often spectacular—fjords, towering mountains, caves, quarries, harbors at night—that he has painted over the years. Brant isn’t interested in landscapes, but “in the energies of the earth, in … things that are real, primordial, alive.” He doesn’t think about the deepest body of water in the United States, Crater Lake, in Oregon, as it is before us, but in how it was formed, by a cataclysmic, geological event: the collapse of a volcano 7500 years ago. This is why the lake is almost perfectly round, its clear, reflective blue surface appearing as a mirror. The gallery, coincidentally, has an unusual, large round window. Before this, Brant has placed a sculpture of a jagged formation on a circular mirror, a formation which echoes with others in the paintings.

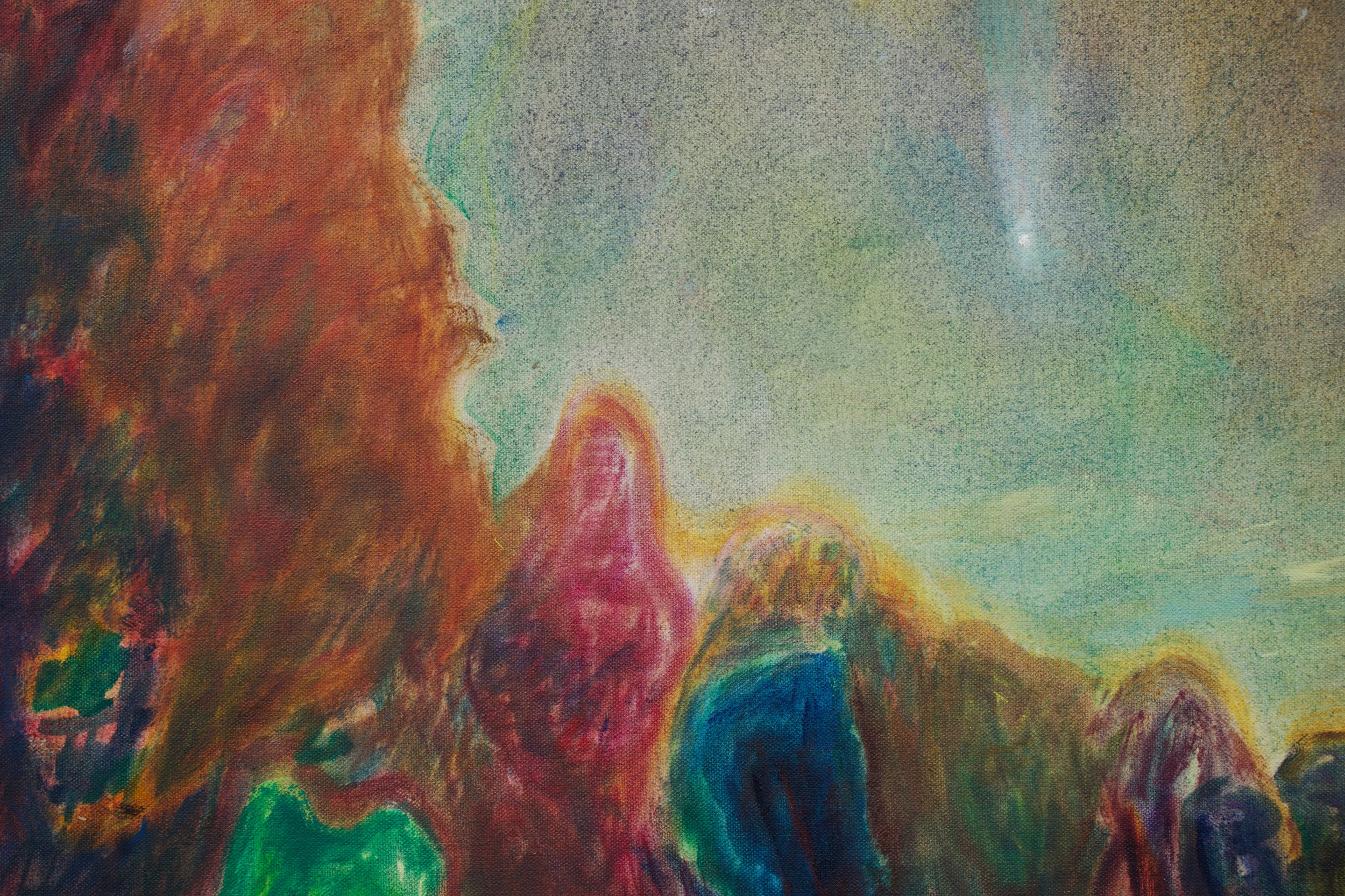

In titling the show Phantom Ship, the artist refers to a lava formation that peaks out above the surface, which appears in a number of these paintings. Although none were painted from life, he visited the lake as an 11-year-old. Painted from photographs, these are clearly painterly improvisations, chromatically and freely rendered, at times verging on abstraction when you observe them in proximity, as he has. In the most atmospheric image, nearly post-Impressionist, when you get up close you discover a solitary figure in a small boat, gazing off into the haze of thin, shroud-like blues and greens and lilac, and palpable stillness. An unexpected apparition as figures only rarely appear in his work. Brant would be reluctant to say that it’s him in the boat, and he contemplated but never returned to the lake in advance of planning this show. Distant memory and a photograph was enough to guide him. To make these paintings of the lake was his return, not only to a place from the past, but to himself as a younger person, “impressed by its depth,” and they serve as a reminder that the fiction of painting is one way of moving through space and time and memory. That’s the landscape: of our mind.

Wells Chandler: Colin Brant Phantom Ship, Europa Gallery June, 2025

Europa is pleased to present Phantom Ship, a solo exhibition featuring a new series of paintings and a ceramic sculpture by Colin Brant. In Phantom Ship, Brant explores the thresholds between geology and mythology, perception and reality, time and timelessness. Drawing on the natural and human narratives of Crater Lake, his paintings become acts of homage and inquiry, meditations on the layered mysteries of place and presence.

Crater Lake, with its perfectly circular basin and island at its center, feels less like a landform than a sacred metaphor etched into the earth by myth itself. Formed nearly 8,000 years ago by the collapse of Mount Mazama in a cataclysmic eruption, it is not merely a crater, it is a cosmic retort, a geological alembic in which deep earthly elements are refined and reborn. Here, geology, myth and alchemy converge in a landscape of transformation.

Renowned for its clarity and symmetry, at 1,943 feet, it is the deepest lake in the United States. Two features rise from its surface, Wizard Island, a volcanic cinder cone and Phantom Ship, a jagged andesite rock formation dating back approximately 400,000 years, resembling a ghostly vessel. Both are remnants of the lake’s violent birth and steeped in lore. Especially evocative in misty conditions, Phantom Ship appears and vanishes in changing light. Wizard Island is said to be protected by a spirit, echoing the beliefs of the Klamath people, for whom the lake is sacred.

A peculiar inhabitant of the lake is “Old Man,” a 30-foot hemlock log that has floated upright for centuries. According to legend, he controls the weather. In 1988, scientists tethered him to the shore during research, only for a sudden snowstorm to descend. Upon release, the weather cleared.

Brant’s recent paintings reflect the physical forms of Crater Lake, while immersing the viewer in its underlying vitality. His practice cultivates direct perception, attuning to a spacious and luminous quality of being. Color and light emerge as central forces. Light moves through compositions as a field of quiet intensity. His palette is subtle, his chromatic shifts measured. Careful, spacious and fully attentive, his process mirrors a contemplative rhythm.

The Klamath name for the lake is Giiwas, meaning “most sacred.” According to their myth, the lake was formed after a cosmic battle between Llao, a malevolent underworld spirit, and Skell, a benevolent sky god. As the mountain collapsed, this mythic conflict imprinted itself onto the land, creating a place of immense power and spiritual danger. Believed as a place of testing, shamanic vision quests were sometimes undertaken nearby, but the lake itself was often avoided, its depth and stillness marked it as a veil between worlds.

Brant’s paintings hold presence; they shift through soft tonalities and atmospheric transitions, evoking the Buddhist tantric concept of the subtle body, an energetic architecture alive, within and around form. His work pulses with interiority, their rhythms echoing the channels and winds of the human body, residing in the felt form of place. Brant’s practice aligns with the Vajrayāna Buddhist visualization of the yidam, a deity chosen for meditative identification and transformation, representing one’s own deepest potential. In this exchange, the yogi merges with the archetype through identification, reshaping the subtle body. The geologies in Brant’s work, quietly offer themselves to this same gesture. They hold still not as an object of worship, but as a mirror reflecting the nature of mind back to itself.

Craters and mountains, depression and elevation, are twin gestures of transformation. The Klamath myth affirms this rhythm through destruction and renewal and descent and ascent. Crater Lake is more than a natural wonder. It is a sacred crucible, a place where the spiritual and geological meet, and where those who approach its depths are invited to enter the ancient cycle of dissolution and rebirth, a rhythm that shapes both the natural world and inner life.

Brant’s paintings position the perceptual vitality of awareness itself as the primary subject. They provide room to slow down and reinhabit our center. They are the profound inseparability of consciousness with the natural world. In this way, his work is not an image of the real, but a mirror of it. And in this nondual reflection, we may catch a glimpse of the reality of ourselves that is still, spacious, and fully alive.

Bob Nickas: Colin Brant: Life-size, 2023 text accompanying exhibition and artists’s book: Colin Brant, Dirty Snowball

Every work of art, even those wholly abstract, are from life, and every work of art is life-size. The subject may be a redwood tree, which in the forest can rise to 380 feet high. Painted, photographed or drawn, the image of the tree may only be a matter of inches, and yet it is life-size to its support, to a sheet of paper, a canvas or a board, to an old postcard. Moreover it is life-size to the eye and the hand of the artist, as well as to the eye of the viewer.

A painting of Godzilla by Colin Brant is very intimately scaled, far from how the monster looms in the imagination or on a movie screen. Godzilla and painting have something in common. Both are fictions. Brant’s painting of the monster is, in fact, life-size. You may guess that it was painted from a toy. You would be wrong. The artist saw the image on the cover of a magazine in the supermarket. The painting is based on a photographic reproduction, as was much of the appropriation art of the 1980s. Colin Brant is not an appropriation artist. He, as is true the world over, has his sources, sources not always from life as understood by way of Impressionism. Any number of images to the contrary, he is not a plein-air painter. Although he may on rare occasion have gone out of his studio to paint, he is primarily studio-based. And no matter how his image appears to us, his subject is always and inevitably painting. And why did he paint Godzilla? That day on the checkout line, he had asked himself, “Can I make a painting of that?”

Most encountering Brant’s work initially would identify him as a landscape painter. He disagrees, not being contrarian, only to insist he’s after something else, something he himself finds hard to explain. He has said that his paintings aren’t “pictures of places,” even as they refer to locations he knows, where he’s from and is now, along with others he has never visited. You don’t have to go to a place to paint it. You go to a place in your mind. Maybe those paintings of where he’s never been are visitations. There can be a reversal of polarity: we don’t go to a place; the place comes to us. The place Brant goes to is painting. The fact of his difficulty to articulate his narrative, and this is neither reluctance nor evasion, is actually helpful in drawing a bead on what he does. Simply stated, what we his viewers see as landscapes is more his own navigating of the terrain, topography, and contours of painting, memory and images and how they intertwine, and how he is relating—and this includes those places he has inhabited—the appearance of the world as seen in his mind’s eye, the act of bringing an image into being. Even a cursory examination of his sources shows that he makes these pictures more alive, vibrant, magical, and at times disorientingly so. The psychedelic, cavernous subterranean room that is Freedley Quarry #2, 2022, for example, might also be described as a spelunker’s hall of funhouse mirrors. In this Brant has something in common with writers whose first duty is to bring a story to life. And what is the painter’s? For both, in relating an actual event or location, the imperative is to make it more interesting, to heighten the experience for readers and viewers. To this end they inevitably intertwine fact and fiction.

When Brant shows us places where we have never been, where he himself hasn’t, he is takes us there, to the painted world. It is itself a map, one that allows him, and us, to get pleasurably lost. This is an artist, painting nearly every day, who often makes multiple variations of an image. Painting, ideally, is recurrent, without final destination. Even as the act of picture-making may be thought of as elliptical, the artist and his followers are never moving from A to B and back again. There is always something else to discover. The realist painter Lois Dodd, now 96, has returned to the same few locations and subjects over and again for the past seven decades—moving between Maine and the Delaware Water Gap, looking out her East Village window—and continues to find engagement. Maybe her picture of a snowy winter day isn’t about the landscape. Maybe it’s about an aloneness, different from loneliness, certainly. Painting, of course, is a solitary activity. It can be a meditation, for artist and viewer alike. The surface of a painting is not dissimilar to a surface of water. There is a mirroring of sky and light from above, peripheral reflection, a wondering of what lies below. To make a painting and to look at a painting share a sense of wonder and curiosity. Consider Colin Brant’s Aquarium, 2023. Observed in proximity, an aquarium is a contained world we put our heads into. The same is true of a painting, or can be. Every painting, no matter the image, is an aquarium of sorts. With Plankton, 2022, Minerals, 2021, and Flower Stand, 2022, Brant arrays everything before us to examine, as he himself has done, and this also holds true for images not directly based on display.

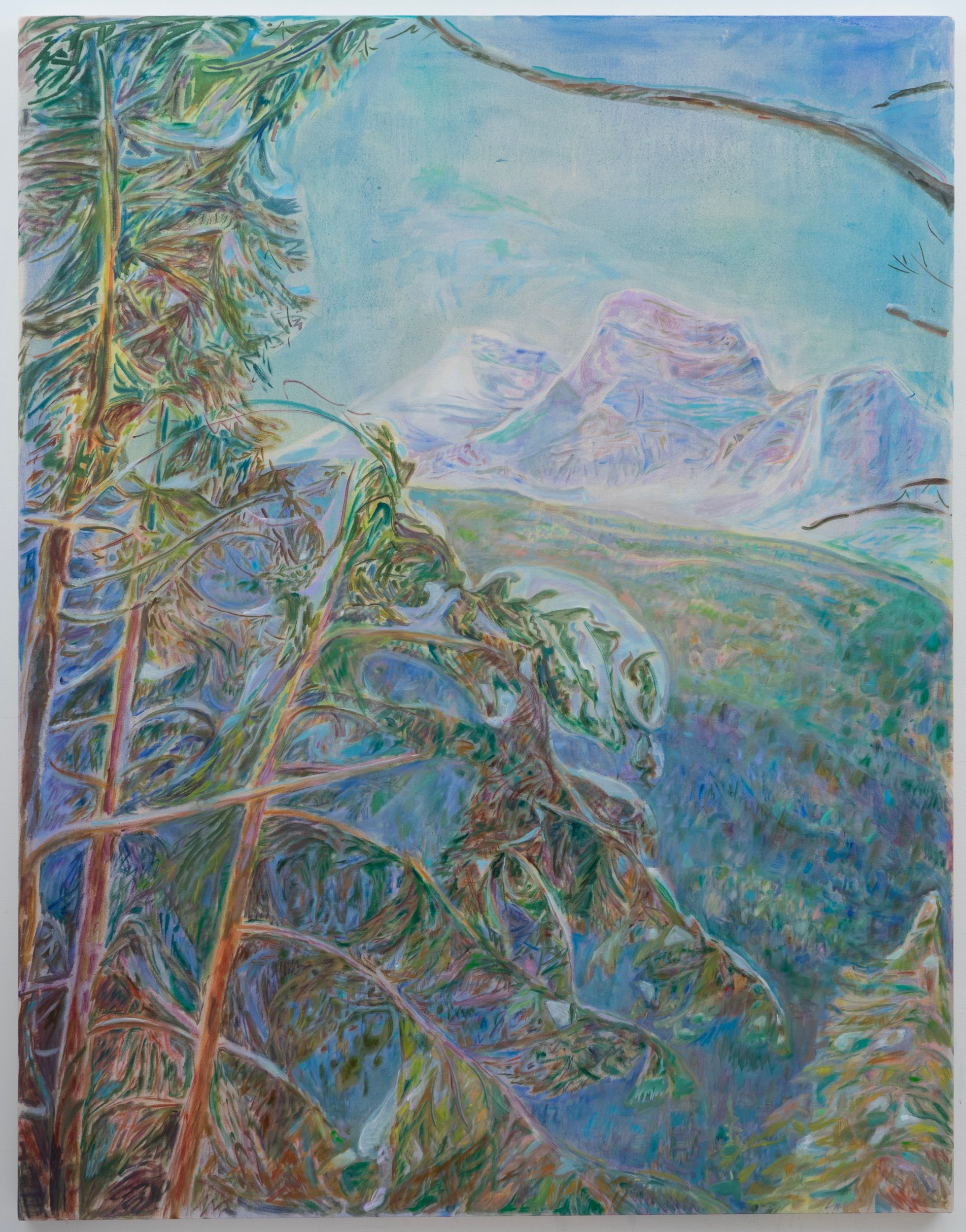

In certain paintings Brant suggests the point-of-view as that of the viewer, an unseen figure in the scene. Grotto, 2023, clearly places the viewer in the painting: on the inside looking out, the cave’s high archway framing the landscape beyond, offering a quietly magical, mystical image. Similarly, Houda Beach, 2022, in Northern California near to where the artist was raised, is framed by nature. In the foreground, left and right, up to the canvas’s midpoint, there are outcrops of grass and rocks; on both sides and along the top, branches with slender feathery leaves ring the inlet and the sea beyond. The viewer stands there, as he was when the source photograph was taken. Despite the vertical format, he moves the eye around a continuous circular path by way of the flow of the marks and serpentine lines at all four sides. This amplifies the sweet spot of the central view, just as it would if we had hiked to the edge of the cliff overlooking the bay, rewarded by the sublime view. More than landscapes, these are images of experiences, including those of the painter in their making. Brant’s painting Moonstone, 2022, which is a beach close to Houda, a near nocturne, might have been painted by Munch in the departure of Northern light, or by Mondrian in his early, revelatory mystic period. Nature, Mondrian knew well, was a spiritual realm. For Brant, “being there” may also encompass distance, and distance foreshortened, as when he transforms his photograph of a diorama in the American Museum of Natural History into an otherworldly vision of an exotic jungle primeval: Congo Forest Diorama AMNH, 2022. With his highly enlivened image, we no longer stand before an enclosed world, a museum simulation, on Central Park West and 79th Street in New York. Looking at his source photo, we more fully see how he has turned a mundane image into something entirely fantastical. Museum dioramas are meant to convey faraway locations or distant points in time as true-to-life, or real. Brant’s imagining of it feels much more actual for its heightened vision. When presented with the grandeur and strangeness of nature, with the sublime, or ridiculously sublime, many of us respond with a single word to convey our impression: Unreal!

Brant has painted numerous fjord scenes, all stunning, although he has never seen one in-person. To look out over a magnificent fjord, this is one place where sublimity resides. More than that, he has an abiding interest in the very creation of the earth, in the planet’s more wondrous, sculptural formations. He knows that the greatest sculptor is nature itself, and often refers in cosmic, microcosmic terms to how life on earth came to be. His 2023 exhibition, Dirty Snowball, borrows its title from the theory proposing that “the building blocks of all life (as well as most of the water) came to earth in the form of giant balls of ice, rock, and dust (comets), that collided with our planet eons ago. In those early primordial swamps amino acids came together to build simple creatures, which turned into more complex creatures …” In the mountain paintings—appearing as clusters of geodes—Brant seems to want to show us what’s inside the stone, how it formed, layer upon layer. He has painted any number of scenes of Lake Louise, in Alberta’s Banff National Park, not only for its beauty and potential for painterly improvisation, but because it is a moraine lake. As such it refers, as fjords do, to glacial time and Earth’s last ice age. The lake’s waters, as rendered in Lake Louise, 2023, appear brilliantly turquoise due to particulate rock dust reflecting light from above. Even Brant’s leaving visible the canvas weave, and the feel of his pigment as at times granular, his color’s rubbed quality, all suggest sedimentary activity. In terms of chromatics, his greens may be described as derived from Chlorophyll, the natural compound in green plants, which gives them their coloration and enables them to absorb the sun’s energy through photosynthesis. From this they generate oxygen. It’s tempting to think of Brant’s work as engaging painting-synthesis, which in his process implicates photography. Far from being made obsolete by the invention of the medium, painting has since the 1820s pointed to the camera’s limitations, certainly of imagination. Of course today everyone takes pictures. Comparatively, very few can paint one.

People appear only infrequently in Brant’s paintings. While there are signs of built structures—a bridge, a house, a hotel—he may be suggesting a world unspoiled by human intervention, an idyllic environment, particularly as we inhabit a planet at greater risk, because of us, to cataclysm. When Brant does include a figure, he usually, by his own admission, hides them. In Mt Sir Donald, 2022, a figure is seated on a rock ledge at the canvas’s center baseline. The source was an old stereoscopic image (accounting for the left/right split that Brant has kept visible, except that it doesn’t bisect the sky), originally sepia, and in his painting greatly hued. The 19th century photographic technique, remarkable in its day, and still, approximates three-dimensional effect. In painting, however, Brant has no need to suggest the illusion of depth. Our depth perception for this image, a canvas measuring 34 by 45 inches (life-size), is a matter of painting’s fictive space, which we inhabit in the act of looking. Here, we grasp how art measures our proximity by degrees. The figure in this painting is small in relation to the vastness of nature and the universe, just as we are. Brant’s distance on the world and the world of images is not measurable in feet and inches. Distance allows him to make these paintings, and allows us to stay close to what he does. He animates and amplifies nature. “I’m not invested in a mountain, a landscape, Godzilla or fish tanks,” he has said, “but in the energies of the earth, glowing things, things that are real, primordial and alive.” He affirms over and again: “We see ourselves in the things we observe.”

Natasha Sweeten: Colin Brant’s Communion with the Inconstant, Two Coats of Paint, November 30, 2023

You might consider the title of Colin Brant’s quietly inspiring exhibition “Mountains Like Rivers,” currently on view at Platform Project Space, an invitation to a world flipped on its end: what’s inherently solid becomes liquid, what’s up is now down. You would not be entirely wrong. Indeed, in Lake Louise/Poppies, the eponymous body of water mirrors the snowy, majestic range that anchors the painting. Red and yellow poppies in the foreground form a joyous tassel punctuating the band of blue, their stems waving like the arms of children eager to be called on.

At a deeper level, the show’s title suggests that the way we see this vast world around us is not a constant; everything everywhere is flush with change. This is not, of course, a new idea. In the sixth century BCE, the Greek Philosopher Heraclitus famously observed that “no man ever steps in the same river twice, for it’s not the same river and he’s not the same man.” Here Brant asks us to look again, to consider this idea from a viewpoint more immediate and less theoretical. His alluring palette, reminiscent of 1940s tinted postcards, elicits a nostalgia for both a time and place that seem familiar, but where I have never been.

The four larger oils – 60 x 50 inches or 60 x 65 inches – encourage us to face the solemnity of Mother Nature and at the same time feel almost casually encountered. In between dabs of paint, the canvases breathe, hinting at a speed or facility in execution and imparting a lightness of touch. In Borca di Cadore, Kodachrome pinks and purples soften a distant rock formation’s boldness, receding into a scenic drapery beyond a thrust of trees jostling for prominence along the painting’s left side. In Lake Louise with Lodge, a bubble of turquoise nestles within a jittery landscape of brushstrokes, as steadfast as the mountains that overlook it. The two-toned lake resists settling quietly into implied space as it reflects the land rising at its edge.

All feels at peace in these paintings – there are no humans around to muck things up. Weaving gestures effected by translucent swabs of color peppered with stumbly brushstrokes create moments of Fauvist vigor, distilling these vistas, at once grand and remote, into a kind of communion. The four smaller oils – 11 by 14 inches or 16 x 14 inches – highlight animals or insects. Perhaps because of the tighter field of vision, there’s less of a sense of wonder here, and they present as more matter-of-fact, like thumbnail images keyed to the wider world depicted in the larger work. They lend structure and cohesion to the show without detracting from its philosophical force. Brant cites the Japanese Buddhist poet Dögen Kigen, post-Impressionists such as Pierre Bonnard, and Chinese landscape painters as inspirations. These influences are clear. The artist steps into the river, and the wide world is new again.

JJ Murphy: Dirty Snowball, Instagram Review, October 2023

With so many high-profile exhibitions right now, it’s easy to overlook some of the most intriguing shows at smaller galleries. Colin Brant’s exhibition “Dirty Snowball” at Dutton Gallery, LES, is one example. Brant’s title refers to the creation of the world, which serves as its major impetus. In the accompanying catalogue essay, Bob Nickas suggests that Brant’s work is largely studio-based. His various “landscapes” are often derived from other sources, such an old stereoscopic image, rather than on actual observed places. The work made me think of the Chicago self-taught artist Joseph Yoakum, who always claimed that his visionary landscapes were a recollection of his earlier travels around the world. Along with Yoakum’s drawings, Brant’s paintings, which have the fluidity of drawings, also relate to the work of John Dilg and Hayley Barker. What about the small-scale painting of “Godzilla (2023)? The source was apparently based on a magazine cover that Brant saw in a supermarket. Could the artist make a painting from it? As a result, it became another source connected to his cosmic project. Brant’s paintings somehow feel otherworldly. Brant’s thin washes of muted color create a swirling vibrancy, that—whether real or imagined—causes the viewer to experience a different realm. One naturally thinks of psychedelic drugs due to the way his paintings pulsate with energy. The work is a far cry from realism. In “Magic Mirror” (2023), for instance, there is a wide discrepancy between the mountainous image and its reflection. In “Lake of the Clouds 2” (2023), warm light illuminates the center, altering our perception of the two different rock formations. As the artist explains, “I’m not invested in a mountain, a landscape, Godzilla or fish tanks, but in the energies of the earth, glowing things, things that are real, primordial and alive.”